The basic geometry of Gothic: the vesica piscis.

Gothic cathedrals synthesize perfectly human ingenuity, the beauty of geometry, and spirituality. They are a testament to an era when knowledge and faith merged to create, through architecture, a connection between the earthly world and the celestial realm. When we step into these spaces, we immerse ourselves in a world where every proportion, every angle, and every shape is part of a geometric language that expresses the search for infinity and the desire to reach heaven. Everything seems designed to impress: the soaring vaults, the colorful stained-glass windows, and the intricate decorative details make us feel small and, at the same time, part of something immense. This stone architecture is a feat of human talent, present in every corner. But what is most fascinating is the technical means and knowledge used to construct these architectural and engineering marvels. At the dawn of the Gothic era, a time when Roman numerals were still used for commerce and the more practical Arabic numerals for calculations and algebra were almost unknown in Europe; the great Gothic cathedrals were built primarily using geometric principles that today are taught to students in the early years of secondary school.

Thus, it is no exaggeration to say that Gothic cathedrals, for their majestic construction and, at the same time, the elegance of the geometric concepts with which they were conceived, are an impressive example of how human ingenuity, the beauty of geometry, and spirituality can come together to create something extraordinary. These cathedrals are not just buildings; they are symbols of an era when knowledge and religion worked hand in hand to connect the earthly world with the heavens. When we enter these spaces, everything seems designed to awe us: the soaring vaults, the colorful stained-glass windows, and the intricate decorative details make us feel small and, at the same time, part of something much more significant. But what is most fascinating is how these wonders were built in an era without the modern tools or mathematical calculations we use today.

To understand the geometry behind these colossal constructions, we must begin with one of the most basic geometric shapes: the equilateral triangle, a symbol in medieval Christianity associated with the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit), representing unity within diversity. However, to construct it using a straightedge and compass, as the master builders of the Middle Ages did, it is necessary to first draw another figure that is one of the most potent symbols of Christianity and the basis of many elements in Gothic architecture: the vesica piscis. The vesica piscis is a geometric figure created by the intersection of two circles of identical radius, where the center of each circle lies on the circumference of the other. This shape, resembling a fish, among other interpretations, was adopted by early Christianity but had already existed under different names and with other meanings in earlier civilizations such as Mesopotamian, African, and Asian cultures.

This fish-shaped figure became a secret symbol of identity and faith for Christians as a collective during the early centuries of persecution in the Roman Empire. This symbol comes from the Greek word “ἰχθύς” (ichthys), which means “fish” and is broken down into an acronym:

- CH: “Christos” (Christ)

- I: “Iesous” (Jesus)

- TH: “Theou” (of God)

- Y: “Yios” (Son)

- S: “Soter” (Savior)

This acronym was a way to encode the essence of Christianity in just a few characters, and it became one of the most recognizable and influential symbols of Christian iconography. In the early centuries of Christianity (1st, 2nd, and 3rd centuries), Ichthys was the equivalent of modern acronyms we use today to condense concepts or identify institutions using the initials of the most important words. For early Christians, ichthys was not just a word but an intrinsically powerful and deeply symbolic message, encapsulating the core beliefs of their faith in five letters. Accompanying this acronym was a “perfect” logo: the vesica piscis, a mystical intersecting shape evoking the image of a fish, which would become the iconic symbol of Christianity. Thus, one could say that ichthys was an impeccable example of branding, skillfully created by early Christians to identify and give form to their faith.

It is fascinating to observe how the vesica piscis, a symbol deeply rooted in Christian iconography, became the essential geometric figure in the construction of cathedrals. Far from being just an ornament, this figure provided a remarkable mathematical proportion, endowing Gothic constructions with unmatched harmony and beauty. It became the omnipresent geometric pattern in the proportions of many elements in these buildings.

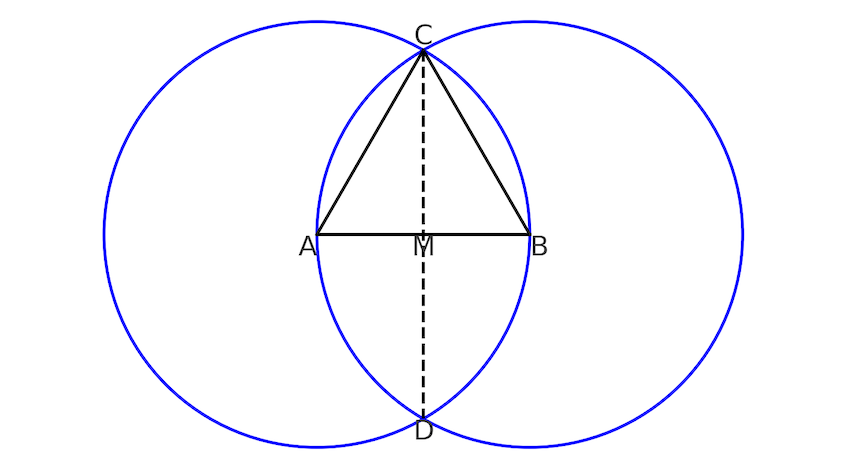

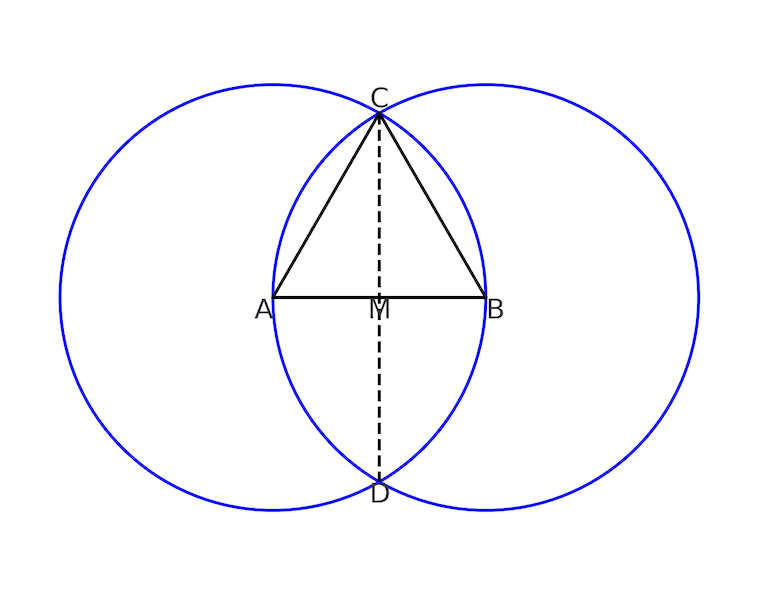

To better understand this harmony, let us examine the following diagram.

In it, we can see how a perfectly inscribed equilateral triangle appears within the vesica piscis at the intersection of two circles. From this, and using the Pythagorean Theorem, we can easily calculate the proportions of this figure. As shown in the diagram, the triangle (ABC) is equilateral and is located precisely at the center of the vesica piscis. Taking (AB = 1), the distance (AM) becomes 1/2.

With these values and using the Pythagorean Theorem, we can calculate the length of (CM):

Thus, the total length of (CD) is twice (CM), that is,

So, the ratio between the length and width of the vesica piscis can be mathematically expressed as:

Obtaining that the square root of 3, an irrational number, is the ratio between the length and the width of the vesica piscis.

Medieval master builders used the vesica piscis to establish the proportions of the most important elements of Gothic cathedrals. This geometric figure can be found in pointed arches, ribbed vaults, naves, windows, and rose windows, among others. It added visual beauty and ensured harmony and structural balance, making these constructions true masterpieces.

In this sense, the most universally recognized Gothic element, the pointed arch, can be easily identified within the vesica piscis if you observe the figure formed by the points A, B, and C at the intersection of the two circles. This pointed shape of the arches is not merely aesthetic; the pointed arch serves a critical structural function. Unlike the semicircular arches of Romanesque architecture, which “push” forces outward and require thick walls to withstand these lateral forces, the pointed arch allowed master builders to direct the weight of all elements vertically downward, toward the bases of the arch. This made it possible to construct taller and more slender structures without the need for massive lateral buttresses.

This design relies on a distribution of forces modeled by the mathematical equation we would express today as:

where F represents the force directed downward, W is the load supported by the arch (i.e., the weight of the vault or the roof), and theta is the angle of the pointed arch. By redirecting the weight toward the bases, medieval builders were able to create luminous spaces with tall, light walls and large openings for stained glass windows. This interplay of forces provided European cathedrals with a technical innovation for the time, seemingly defying gravity.

Nevertheless, as technically advanced as this type of construction might seem for its era, we must keep in mind a fundamental detail that cannot be overlooked: the master builders of the time did not have access to algebraic calculations or equations like the ones presented in this article to construct Gothic cathedrals. They lacked modern tools and advanced mathematical knowledge, which we now see as essential for executing a construction project. However, they possessed deep practical knowledge, accumulating and passed down through generations. This experience allowed them to understand with great precision how forces and weight distribution worked within their colossal constructions, achieving results that continue to fascinate us centuries later.

In this sense, it is worth remembering that although trigonometry — the branch of mathematics that studies angles and distances — was already known to ancient cultures like the Babylonians, in 12th-century Europe, at the dawn of the Gothic period, they were just becoming aware of the existence of the number zero. Roman numerals were still being used for calculations. What does this imply? It means that master builders could not carry out the structural design of cathedrals based on numerical estimates, as Roman numerals were not practical for complex calculations required in construction. To see progress in this regard, we must move forward to the 13th century. At that time, the renowned Italian mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci wrote his Liber Abaci (1202), with the purpose of introducing and popularizing the Arabic-Hindu numeral system in Europe, using the digits 0 to 9 and the concept of zero as we use them today as a basis for calculations. This system was far more practical for calculations and trigonometry than the Roman numeral system, which, as mentioned, was dominant in Europe at the time but less efficient for computation. However, it would still take centuries for these calculation methods to become widely adopted in all areas of society, including architecture and construction in Europe.

Another characteristic element of Gothic architecture, the ribbed vaults of the naves—a fundamental component of the structure of Gothic cathedrals—also relies on the vesica piscis as an essential element in its design. Formed by the intersection of pointed arches, these vaults create a network of lines that distribute weight with precision, using the principle of ruled surfaces. Gothic master builders meticulously crafted each rib to ensure the vault could support the weight without compromising the stability of the building.

As for the stained-glass windows and rose windows of Gothic cathedrals, these elements are also prime visual examples of how the vesica piscis became a fundamental basis for both proportions and decorative designs. This geometric figure is not only present and influential in the general dimensions of these elements but also manifests in their intricate patterns. The master builders and glass artisans of the time developed an impressive skill, given the means available, creating tangent circles, regular polygons, and star-shaped figures within them, combining glass and stone with precision to bring these masterpieces to life. The complexity of these designs reflects a deep understanding of geometry and an extraordinary technical capability. Regarding this topic—the stained-glass windows and rose windows of Gothic cathedrals—due to their complexity and the sheer number of details they contain, I will address it in another publication to provide a thoughtful and detailed explanation of the relationship between proportions, the geometry of these ornamental elements, and the vesica piscis.

In an era without complex calculations or modern tools, the master builders erected these colossal structures using geometry, intuition, and knowledge passed down from generation to generation. Geometry was a technical resource and a way to connect with the divine. Among all the geometric figures that sustain this legacy, the vesica piscis stands out as a symbol of harmony and transcendence. This figure, created, as we have seen, by the intersection of two circles of identical radii, where the perimeter of each passes through the center of the other, became not only a spiritual emblem but also the basis for designing the proportions and forms of key elements in cathedrals, such as pointed arches, ribbed vaults, windows, and rose windows, among others. The vesica piscis, with the equilateral triangle within it, reminds us how the inherent beauty of geometry can be both functional and symbolic. This symbol, which unites mysticism and technical precision, reflects the rich interconnection of the Middle Ages between science and faith, between humanity and the divine. Gothic cathedrals, therefore, are not merely imposing buildings but true works of art that integrate mathematical, philosophical, and spiritual knowledge. They remind us of humanity’s ability to understand and shape what seems impossible. This architectural legacy continues to inspire and amaze those who behold them, offering a window into an era when mathematics and geometry were considered a pathway to understanding the cosmos and its inherent beauty.