2024: A Record Year for Global CO₂ Emissions from Fossil Fuels – But Why?

Introduction.

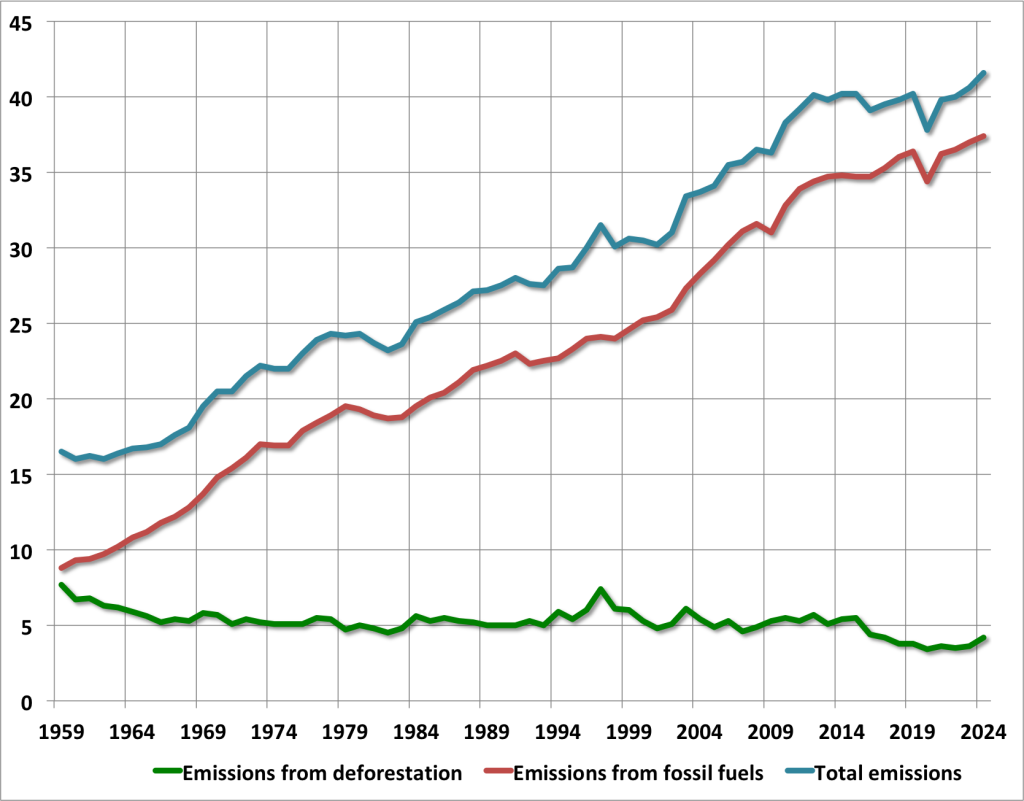

As 2025 begins, it is time to assess the data published regarding global carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions for 2024. Unfortunately, according to estimates released recently, these data show that during the year we have just left behind, global emissions, far from decreasing, have continued to rise, reaching 41.6 billion tons of CO₂. This figure indicates that the volume of CO₂ emissions in a single year has reached a new historical high, surpassing 40.6 billion tons in 2023.

These data are concerning because they show that, despite international commitments, current policies to reduce CO₂ emissions remain insufficient to achieve an effective reduction. Moreover, although many countries are making significant investments to reverse this situation, the reality of global annual CO₂ emissions data makes it clear that we have not yet achieved the goal of curbing their increase. Unfortunately, this also means that we are not yet in a position to slow down global warming.

Global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuel consumption.

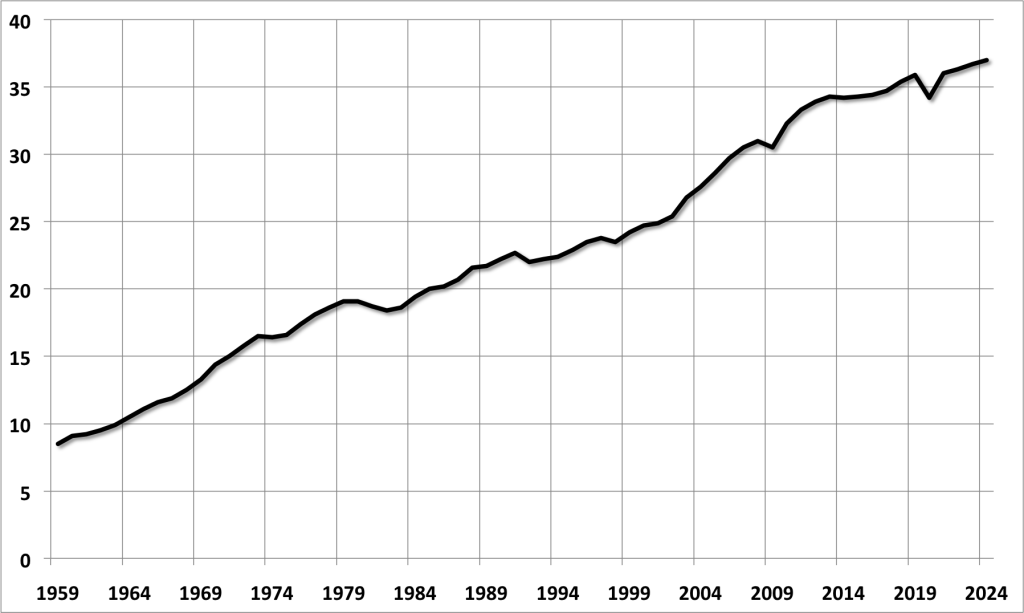

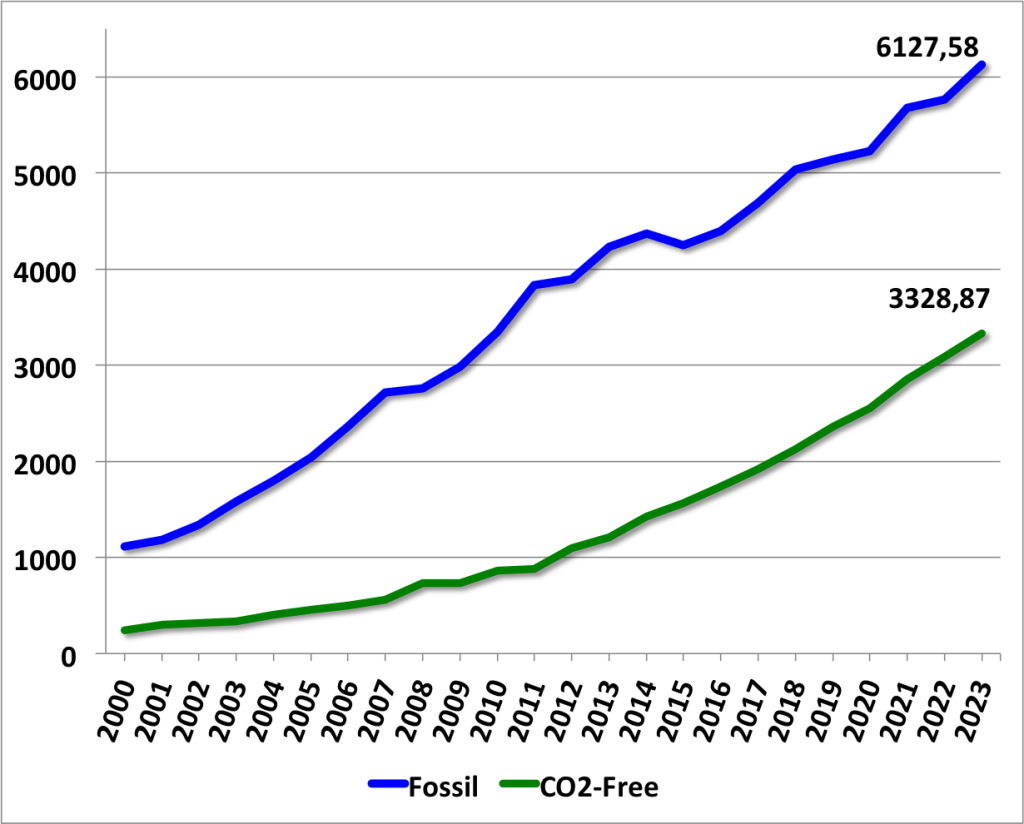

According to the Global Carbon Project1 report, in 2024, emissions from using fossil fuels, which account for the majority of global emissions, failed to decrease and increased, reaching 37.4 billion tons of CO₂. This represents a 0.8% rise compared to emissions in 2023. This growth is primarily explained by the increase in global consumption of the three primary fossil fuels in 2024:

- Natural gas’s global consumption increased by 2.4%, accounting for 21% of total CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels.

- Oil consumption rose by 0.9%, representing 32% of global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels.

- Coal, which, despite a more modest increase of 0.2%, remains the largest contributor to global emissions associated with fossil fuels, accounting for 41% of the total.

Graph 1 – Annual Global CO₂ Emissions from Fossil Fuels. Data in Gt of CO₂. Source: Global Carbon Budget 2024.

These data reveal that fossil fuels remain the primary energy source despite international efforts and commitments and significant global investments in solar photovoltaics and wind energy technologies. This is particularly evident in countries like India and China, which, far from stabilizing or reducing electricity production from fossil fuel sources, are still constructing new power plants with capacities of several gigawatts, where coal will be the primary fuel used. The consequence of this is a growing demand for coal in these two Asian countries, which, according to the International Energy Agency, will lead to a continued rise in global coal consumption over the coming years, at least until 2028-2030.

Global CO₂ emissions from deforestation and land use.

In addition to CO₂ emissions from using fossil fuels in 2024, a second source of emissions must be included to calculate the total annual CO₂ emissions: emissions associated with deforestation and land expansion for agricultural purposes. According to the Global Carbon Project report, emissions from deforestation and land-use change in 2024 are estimated at 4.2 gigatons of CO₂. While this global emission volume is much lower, in absolute terms, than that of emissions from fossil fuel use, this does not mean it should not be considered significant. On the contrary, the impact of deforestation and agricultural land expansion has a dual negative effect on CO₂ emissions. On the one hand, it contributes directly to the increase in CO₂ in the atmosphere. On the other, the destruction of natural sinks like forests, wetlands, and other ecosystems that act as essential regulators of the carbon cycle decreases the planet’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide.

According to reports published by international organizations such as the FAO, World Wildlife Fund, and Global Forest Watch, this issue is particularly severe in regions like the Amazon and Southeast Asia. Deforestation is accelerating biodiversity loss and disrupting ecosystems locally and globally. This endangers the survival of many species and weakens the planet’s ability to regulate the climate, exacerbating the effects of climate change even further.

Thus, when emissions from deforestation and land-use changes are added to those from fossil fuel use, the total global CO₂ emissions for 2024 amount to 41.6 billion tons of CO₂. This total emissions volume for 2024 represents a 2.5% increase compared to 2023, and forthcoming projections indicate that global annual CO₂ emissions will continue to rise in the coming years, at least until the end of this decade. Halting this increase earlier than current forecasts predict is a critical challenge to at least slow down the current process of global warming and advance toward a more sustainable energy and environmental model.

CO₂ emissions by world regions.

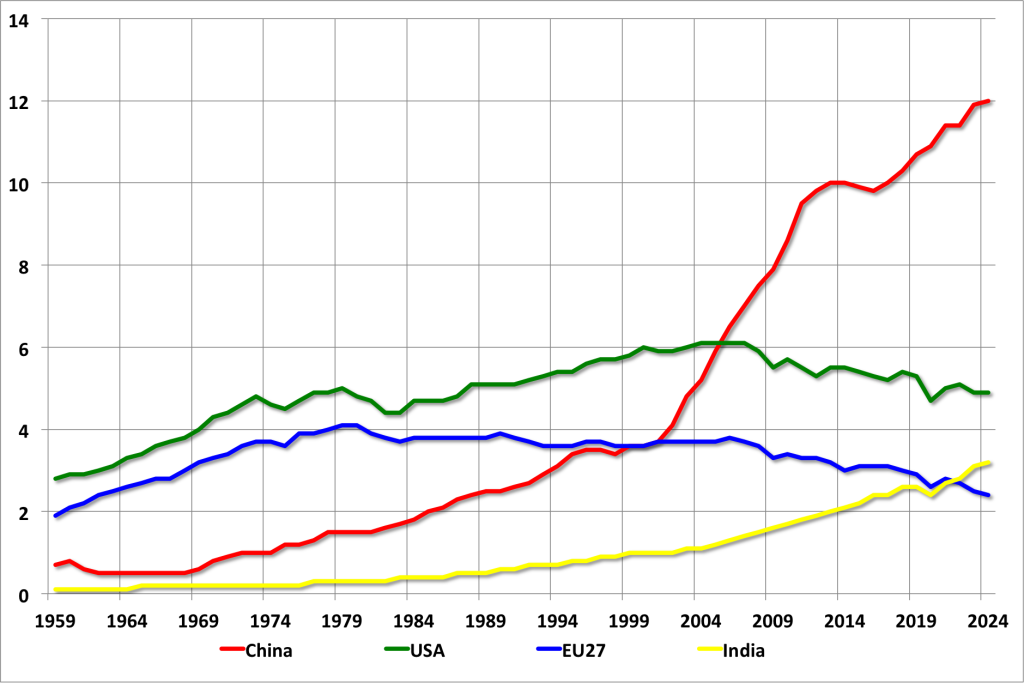

Suppose we focus on emissions from fossil fuel consumption, but this time analyze them by world region. In that case, the data reveals significant differences between emissions generated in Asia, Europe, and the United States. In Asia, China and India are the main contributors to emissions, with levels far exceeding those of any other Asian country.

India, which since 2023 has been the most populous country in the world with 1.43 billion inhabitants, increased its CO₂ emissions by 4.6% in 2024, reaching a total of 3.2 gigatons. This increase is partly explained by the Indian government’s strategy to boost economic growth, which has led to higher energy demand in the country. All indications are that this upward trend in CO₂ emissions will continue in the coming years. In this regard, according to press releases from Indian government sources2, the government’s forecasts show that greenhouse gas emissions will continue to rise in the coming years, driven by economic growth policies and poverty eradication efforts.

However, on the other hand, the Indian government intends to reduce the carbon intensity per unit of GDP3 by 45% by 2030, using 2005 emission levels as a baseline, and achieve carbon neutrality by 2070. An example of this commitment is the project currently under construction in Gujarat (India) called Khavda Solar Park, which is expected to be completed by 2026. According to announcements, this will be the world’s largest hybrid renewable energy park (solar and wind), with a capacity of 30 GW, combining solar and wind energy. The park will cover an area of 72,600 hectares and is expected to supply energy equivalent to the consumption of 18 million Indian households. Moreover, the project is expected to generate approximately 100,000 jobs and reduce India’s CO₂ emissions by 50 million tons annually.

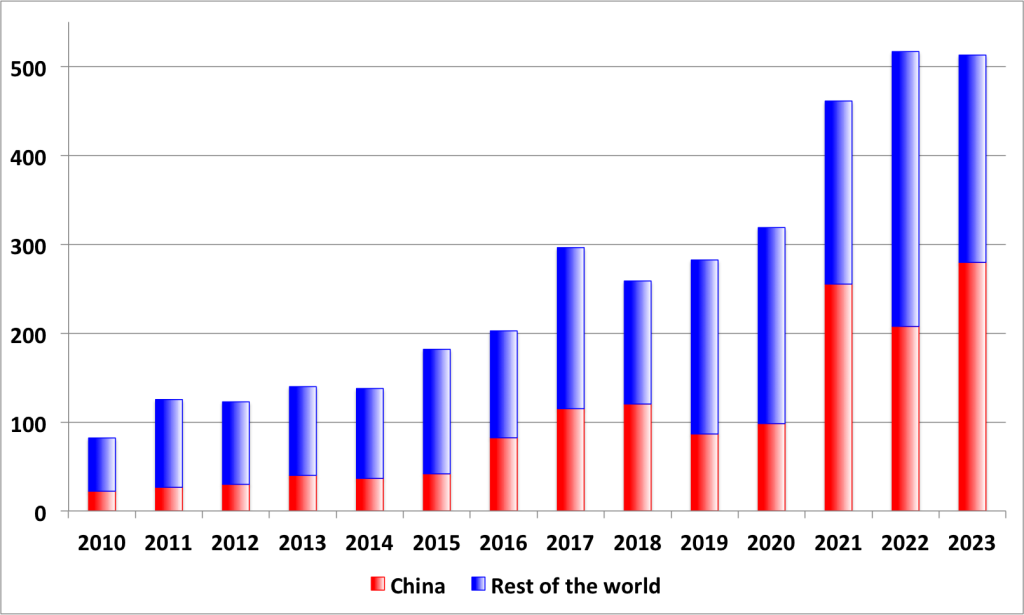

Regarding China, its CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels remain significantly higher than India’s. The Asian giant is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide, primarily due to its high coal consumption, making it the largest consumer of coal globally. In 2024, China generated 12 gigatons of CO₂, accounting for approximately 32% of the 37.4 gigatons emitted worldwide from fossil fuel consumption. This figure underscores China’s central role in the global CO₂ emissions landscape.

However, it is worth noting that despite its position as the world’s leading CO₂ emitter, China’s energy situation presents an interesting paradox. On the one hand, its high energy demand makes it the most significant global consumer of coal, which accounts for 56% of its electricity generation. On the other hand, China is, by far, the leading international investor in renewable energy in a remarkable way. A clear example of this is that, recently, China has consistently led the annual installation of new renewable capacity to the extent that in 2023 and 2024, China added more than half of the new solar and wind generation capacity installed worldwide to its electric grid. This sustained effort has made China the world’s largest producer of electricity from renewable sources.

Thus, thanks to its consistent efforts to expand renewable energy within its territory—essential for ensuring energy security and driving economic growth—China has significantly increased its energy production without a substantial rise in CO₂ emissions. In this regard, although official data on China’s total energy production in 2024 is not yet available, estimates suggest an increase in electricity generation of between 650 and 950 TWh compared to 2023. In percentage terms, this represents a growth of 7% to 10% compared to 2023. However, regarding CO₂ emissions, preliminary data indicates that these rose by only 0.2% compared to the previous year, increasing from 11.9 gigatons to 12 gigatons.

This moderation in the emissions increase reflects the positive impact of China’s significant capacity for electricity generation from renewable energy sources. However, it also highlights the difficulty of decarbonizing an energy system as energy demand grows significantly yearly. Despite the progress China has made in renewable energy generation, the constant increase in its energy demand and its heavy reliance on fossil fuels, which generate more than 50% of its energy, has meant that recently, China has still not been able to reduce its carbon intensity per unit of GDP significantly. This situation underscores the complexity of balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability in a large-scale economy. Achieving this requires not only improving energy efficiency and making consistent investments in renewable energy sources but also gradually reducing dependence on fossil fuels and implementing measures to ensure that gains in energy efficiency are not offset by an even more significant increase in energy demand.

As for Europe and the United States’ current CO₂, emissions dynamics in 2024 were very different from those observed in Asia. Europe and the United States continued to see emissions decline in 2024, maintaining the trend of recent years. In the European Union, total CO₂ emissions in 2024 were 2.4 gigatons, representing a 3.8% decrease compared to 2023. The reasons for this reduction lie in the efforts made by member countries to reduce fossil fuel use and promote the increase in renewable energy sources, which already account for more than 40% of the energy mix in many EU countries.

Regarding the United States, emissions also decreased, although more modestly. CO₂ emissions in the United States in 2024 stood at 4.9 gigatons, a 0.6% reduction compared to the previous year. This reduction is primarily attributed to federal government efforts to promote electric vehicles and invest in solar and wind energy in recent years. Additionally, the country has significantly increased investments in renewable energy, particularly in solar and wind power, which have experienced sustained growth thanks to policies such as tax credits for businesses and individuals. These new investments in renewable sources are gradually beginning to replace coal and natural gas for electricity generation in some states, thereby helping to reduce emissions from the energy sector, one of the country’s most polluting sectors. However, the extent of the reduction remains limited due to the high energy consumption levels in the United States, particularly in sectors such as transportation and industry, which still rely heavily on fossil fuels.

Rising energy demand: a barrier to global electric system decarbonization.

Thus, although the data shows that regions like Europe or the United States have exhibited trends of continuous year-on-year reductions in CO₂ emissions for some time now, this is not the case globally. The data indicates that fossil fuels remain the planet’s primary energy source despite international commitments to reduce CO₂ emissions.

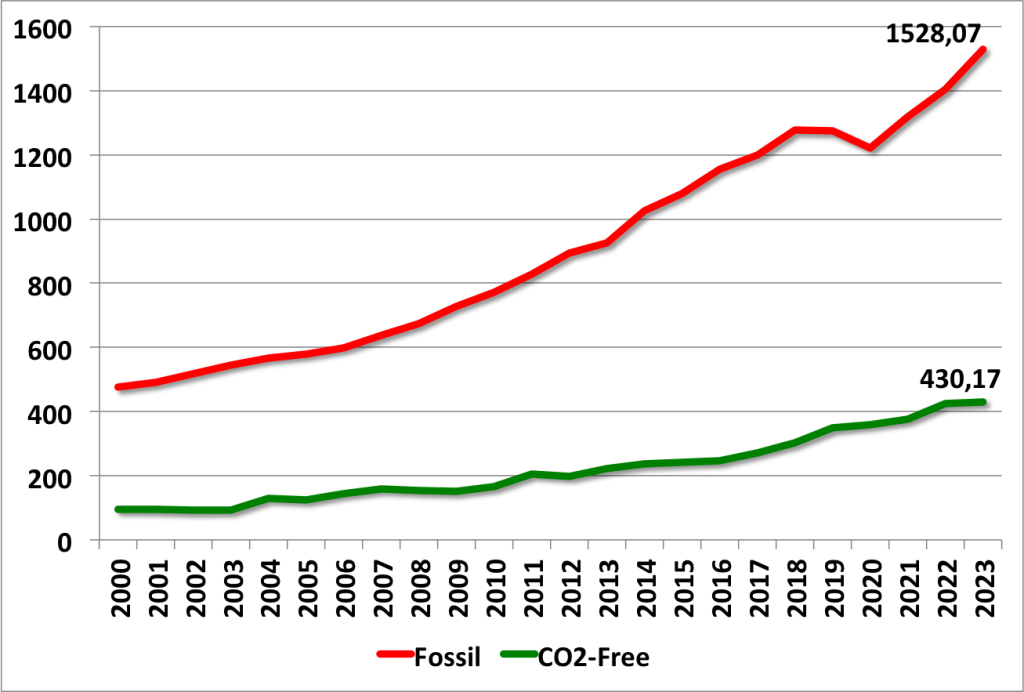

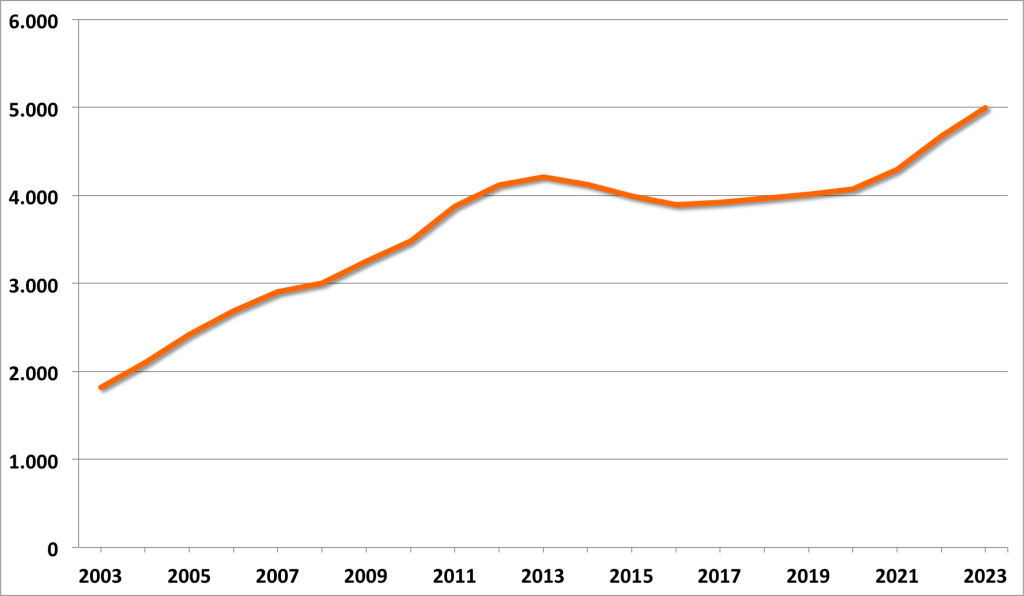

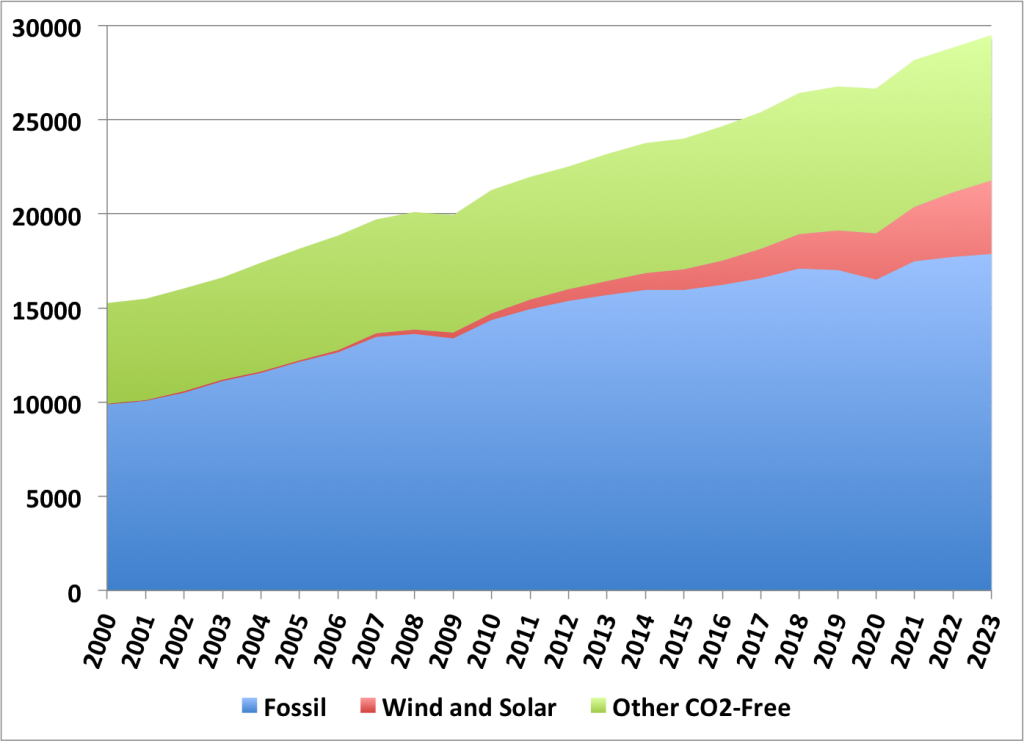

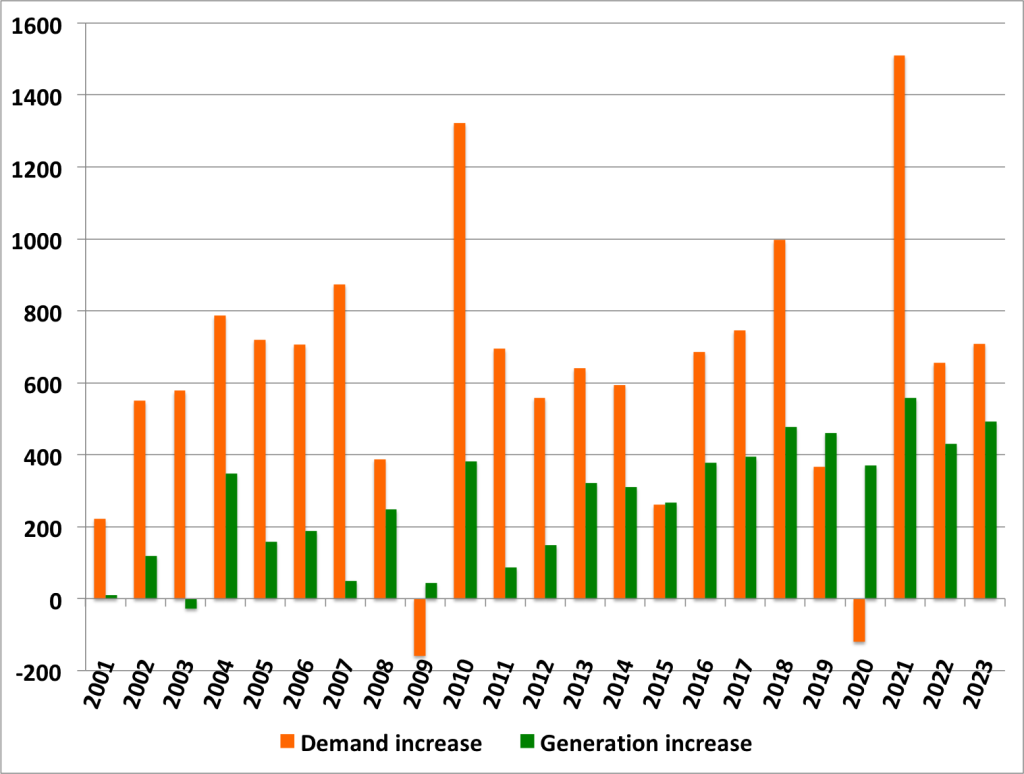

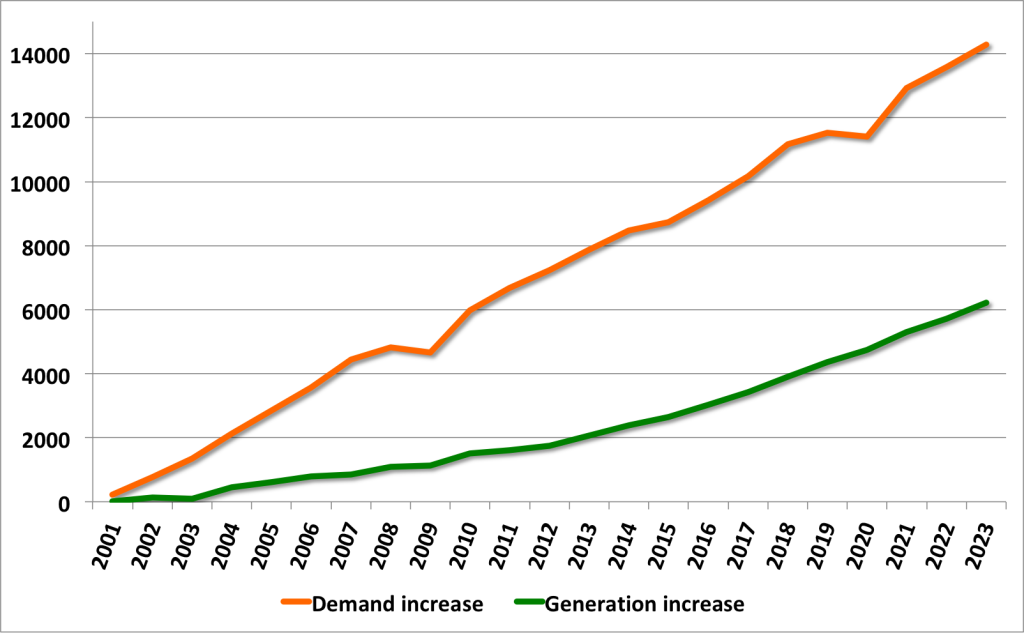

Even though energy production from renewable technologies is growing steadily and at an increasingly rapid pace, this increase is insufficient to meet the rise in global energy demand, which continues to grow yearly. This means the world requires more energy each year instead of reducing annual energy needs. As shown in graphs 9 and 10, there is a clear imbalance between the global capacity to add new renewable energy generation annually and the more significant increase in energy demand. Although annual investments in renewable energy are growing, the energy needed is increasing faster than the capacity to produce it with the installed clean sources. This results in an accumulating gap each year between the number of new TWh the world requires and the number of new TWh the world can generate with renewable sources. This phenomenon makes the goal of decarbonizing the electric system increasingly difficult to achieve. This reality underscores the need to intensify actions to balance the scale between renewable energy generation and energy demand.

In summary, the increase in energy demand, driven by the growth of emerging economies and the rise of the global population, highlights that accelerating the energy transition is essential to decarbonizing the global economy within a few decades. Furthermore, developed economies must significantly reduce energy consumption and commit to energy efficiency worldwide. At the current rate of CO₂ emissions, without implementing a more ambitious and coordinated reduction policy worldwide, it will be challenging to achieve the climate neutrality targets set for the coming decades. This would lead to an aggravation of climate change consequences, significantly affecting all regions.

Consequences of the continuous increase in global CO₂ emissions

Thus, under this scenario of continuous growth in global energy demand, the data from the published estimates of 2024 CO₂ emissions reveal that, despite technological advances in performance and energy efficiency, international commitments to combat climate change, and efforts to mobilize the necessary financing for new investments in renewable energy plants, global CO₂ emissions continue to rise year after year. Unfortunately, this trend has consequences, as confirmed by data collected from various international organizations.

Among these consequences is the increase in atmospheric CO₂ concentration, which rose again in 2024. According to estimates from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), it reached 422.5 parts per million (ppm)4, an increase of 2.8 ppm compared to 2023. This means the current atmospheric CO₂ concentration is approximately 52% higher than 175 years ago.

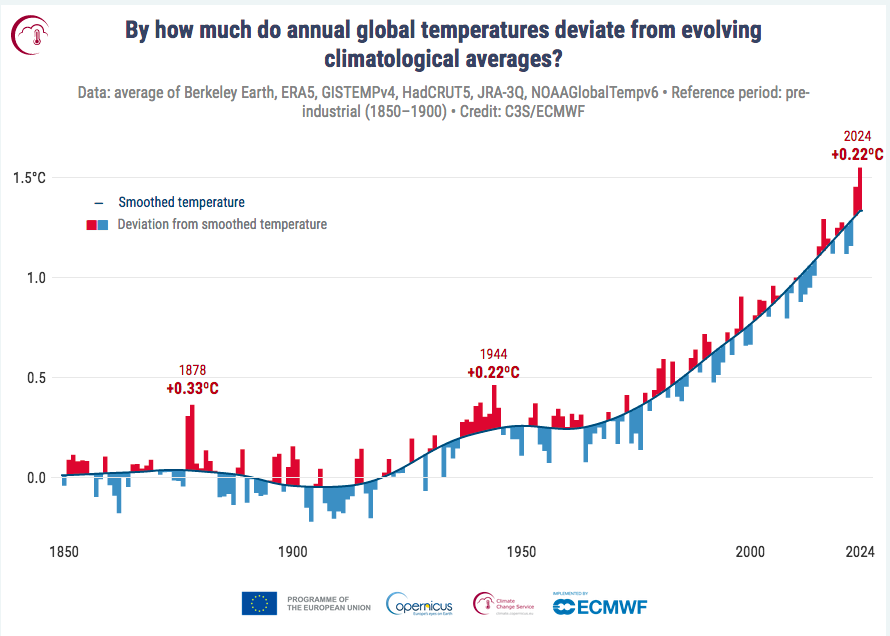

Another consequence is the rise in global temperatures. According to the final 2024 report from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S)5, published in January 2025, 2024 was the warmest year on record since 1850. The global average temperature reached 15.10°C, surpassing the 2023 record by 0.12°C and 1.60°C above the pre-industrial average. Thus, 2024 becomes the first year to exceed the critical threshold of 1.5°C set by the Paris Agreement6. Furthermore, to underscore the gravity of this situation, the 2024 data indicate that the past year was 0.72°C warmer than the 1991–2020 average, solidifying the decade from 2015 to 2024 as the warmest on record, demonstrating a troubling acceleration in global warming.

Another consequence of the global increase in CO2 emissions is the rise of extreme weather events, which have shifted from future predictions to present realities. These phenomena are increasingly frequent worldwide and have a direct and tangible impact on ecosystems and the human societies affected by them. In this regard, 2024 provided examples that remain vividly in our minds. In Catalonia, for instance, persistent droughts over recent years have drastically reduced water resources, increasing pressure on water supply across much of the region. In Valencia, the floods caused by the 2024 DANA resulted in unprecedented devastation, severely affecting infrastructure and communities. At the beginning of 2025, Los Angeles faced a devastating wildfire that destroyed entire neighborhoods. This fire, fueled by the strong winds typical of the region at this time of year, was exacerbated by dry vegetation after months of severe drought, creating ideal conditions for the flames to spread rapidly, making containment almost impossible.

This reality, reflected in the scientific data collected and the rise in extreme climate events experienced worldwide, underscores the urgent and unavoidable need for effective and coordinated global measures to reduce CO2 emissions. While we cannot wholly halt climate change, we must strive to mitigate its already existing effects.

Conclusions.

With the 2024 data in our hands, it is confirmed that the use of fossil fuels, far from decreasing, has once again increased globally. Consequently, annual CO₂ emissions have also continued to rise, exacerbating global climate warming and the frequency of extreme weather events worldwide.

Unfortunately, despite the growing efforts made over the past decade to improve energy efficiency and increase energy production from renewable sources, global energy demand has grown even faster. This situation has necessitated bridging the gap between the energy required, and the energy generated from renewables through fossil fuels, perpetuating a persistent dependence on these sources. The result is that we are not only failing to reduce fossil fuel consumption, but paradoxically, it continues to increase year after year. This dynamic complicates—and may even obstruct—the transition to a CO₂-neutral energy model in the short and medium term. Furthermore, it is important to note that projections indicate this situation will worsen significantly in the coming decade, as new annual energy demand is expected to grow at a much faster rate than in the past decade. This increase will be driven by factors such as the expansion of energy consumption in data centers, the development of artificial intelligence7, the consolidation of electric vehicles in developed societies, and other emerging energy demands that will arise.

To break this vicious cycle, we cannot assume that current measures are sufficient, no matter how significant they may seem. It is essential to broaden the range of actions and rethink key strategies. While we still lack the technological capacity to generate all global energy exclusively from clean sources, we have the knowledge and tools to tackle future challenges. It is crucial to transform the linear growth of renewable energy generation into exponential growth, improve energy efficiency, and eliminate unnecessary consumption. Additionally, the economic viability of existing but underutilized technologies must be developed, such as local biomethane production from biomass, the expansion of energy storage systems—whether through batteries or pumped hydro storage—and promoting self-consumption in both domestic and industrial sectors. Only by combining these efforts and developing new energy vectors can we significantly reduce dependence on fossil fuels and move toward a more sustainable and resilient energy system, without reducing the capacity to create wealth to meet society’s needs and advance technologically and scientifically.

However, it must be clear that addressing this challenge will not depend solely on technology or the actions of a few countries; it will require a collective effort on a global scale, involving profound changes in how we live, produce, and consume. If, as a society, we aim to avoid a climate and economic crisis in the coming decades, it is essential to urgently rethink key aspects such as the model for energy generation and consumption, the management of natural resources, and the preservation of the planet’s major green lungs.

In light of this reality, two essential questions arise that are key to truly addressing the problem of global CO₂ emissions and climate warming: Are we, as a society, sufficiently aware of the magnitude of the situation and the consequences that an even greater increase in global temperature will have on our societies? And, if so, is the international community united enough to face this challenge together?

- https://globalcarbonbudget.org/fossil-fuel-co2-emissions-increase-again-in-2024/ ↩︎

- https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1945472 ↩︎

- CO₂ intensity refers to the amount of carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions generated per unit of economic activity, usually expressed in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Practically, it measures the efficiency with which an economy uses energy and resources to generate wealth concerning its CO₂ emissions. This data is significant because it indicates the CO₂ emissions produced for each unit of wealth created (GDP). In other words, it shows whether a country is managing to generate more wealth while using less energy that emits CO₂, a crucial aspect for reconciling economic growth with the fight against climate change and sustainability.

It is calculated as follows:

CO₂ Intensity = CO₂ Emissions (tons) / Constant GDP (monetary units)

In 2023, global CO₂ intensity (CO₂ emissions per unit of constant GDP) decreased by 1.5%, slower than in 2022 (2%) and the annual average during 2010–2019 (1.9%). However, thanks to reduced energy consumption and increased CO₂-free energy generation, CO₂ intensity dropped significantly (and at a much faster pace than during 2010–2019) in OECD countries such as the United States (-4.3%), Japan (-8.7%), and South Korea (-5.4%). CO₂ intensity also declined by 8.8% in the EU (due to increased nuclear and renewable energy generation, as in Japan and South Korea, as well as hydropower), 5.9% in the United Kingdom, and 2.3% in Canada. Conversely, CO₂ intensity rose slightly in Australia (+0.9%) and Mexico (+2.4%).

In BRICS countries, the reduction in CO₂ intensity is slowing: from -2.6% annually during 2010–2019 to a decline of -0.9% in 2022 and -0.6% in 2023. Specifically, in China, CO₂ intensity has remained stable in recent years, contrasting with the -4.2% annual decline observed during 2010–2019. In other BRICS nations, Brazil experienced only a -0.6% drop, India -0.6%, Russia -2.6%, and South Africa -2.3% (due to coal and electricity supply issues).

Source: https://datos.enerdata.net/co2/intensidad-mundial-CO2.html ↩︎ - According to the recommendations established by climatologist James Hansen (currently an adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, where he has directed the Climate Science, Awareness, and Solutions Program since 2013, and director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York from 1981 to 2013) and other scientists, 350 parts per million (ppm) of CO₂ in the atmosphere is considered the safe limit to stabilize the climate and prevent irreversible changes in natural systems. ↩︎

- https://climate.copernicus.eu/global-climate-highlights-2024 ↩︎

- The 1.5 °C limit was officially established with the Paris Agreement in 2015, during the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In this agreement, countries committed to keeping the increase in global average temperature well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to continuing efforts to limit this increase to 1.5 °C, as this limit is considered essential to reduce the risks and impacts of climate change significantly. ↩︎

- https://b54engineering.com/en/energy_consumption_ai_241129/ ↩︎